Let's say that you aim -- as most people do -- to be morally mediocre. You aim, that is, not to be morally good (or non-bad) by absolute standards but rather to be about as morally good as your peers, neither especially better nor especially worse. Suppose also that you are in some respects ethically ignorant. You think that A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H are morally good and that I, J, K, L, M, N, O, and P are morally bad, but in fact you're wrong 25% of the time: A, B, C, L, E, F, G, and P are good and the others are bad. (It might be better to do this exercise with a "morally neutral" category also, and 25% is a toy error rate that is probably too high -- but let's ignore such complications, since this is tricky enough as it is.)

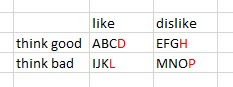

Finally, suppose that some of these acts you'd be inclined to do independently of their moral status: They're enjoyable, or they advance your interests. The others you'd prefer not to do, except to the extent that they are morally good and you want to do enough morally good things to hit the sweet zone of moral mediocrity. The acts you'd like to do are A, B, C, D, I, J, K, and L. This yields the following table, with the acts whose moral valence you're wrong about indicated in red:

Now, what acts will you choose to perform? Clearly A, B, C, and D, since you're inclined toward them and you think they are morally good (e.g., hugging your kids). And clearly not M, N, O, and P, since you're disinclined toward them and you think they are morally bad (e.g., stealing someone's bad sandwich). Acts E, F, G, and H are contrary to your inclinations but you figure you should do your share of them (e.g., serving on annoying committees, retrieving a piece of litter that the wind whipped out of your hand). Acts I, J, K, and L are tempting: You're inclined toward them but you see them as morally bad (e.g., taking an extra piece of cake when there isn't quite enough to go around). Suppose then that you choose to do E, F, I, and J in addition to A, B, C, and D: two good acts that you'd otherwise to disinclined to do (E and F) and two bad acts that you permit yourself to be tempted into (I and J).

Continuing our unrealistic idealizations, let's count up a prudential (that is, self-interested) score and moral score by giving each act a +1 or -1 in each category. Your prudential score will be +4 (+6 for A, B, C, D, I, and J, and -2 for E and F). Your own estimation of your moral score will also be +4 (+6 for A, B, C, D, E, and F, and -2 for I and J). This might be the mediocre sweet spot you're aiming for, short of the self-sacrificial saint (prudential 0, moral +8) but not as bad as the completely selfish person (prudential +8, moral 0). Looking around at your peers, maybe you judge them to be on average around +2 or +3, so a +4 lets you feel just slightly morally better than average.

Of course, in this model you've made some moral mistakes. Your actual moral score will only be +2 (+5 for A, B, C, E, and F, and -3 for D, I, and J). You're wrong about D. (Maybe D is complimenting someone in a way you think is kind but is actually objectionably sexist.) Thus, unsurprisingly, in moral ignorance we might overestimate our own morality. Aiming to be a little morally better than average might, on average, result in hitting the moral average, given moral ignorance.

Let's think of "ethical efficiency" as one's ability to squeeze the most moral juice from the least prudential sacrifice. If you're aiming for a moral score of +4, how can you do so with the least compromise to your prudential score? Your ignorance impairs you. You might think that by doing E and F and refraining from K and L, you're hitting +4, while also maintaining a prudential +4, but actually you've missed your moral target. You'd have done better to choose L instead of D -- an action as attractive as D but moral instead of (as you think) immoral (maybe you're a religious conservative and L is starting up a homosexual relationship with a friend who is attracted to you). Similarly, H would have been an inefficient choice: a prudential sacrifice for a moral loss instead of (as you think) a moral gain (e.g., fighting for a bad cause).

Perhaps this is schematic to the point of being silly. But I think the root idea makes sense. If you're aiming for some middling moral target rather than being governed by absolute standards, and if in the course of that aiming you are balancing prudential goods against moral goods, the more moral knowledge you have, the more effective you ought to be in efficiently trading off prudential goods for moral ones, getting the most moral bang for your buck. This is even clearer if we model the decisions with scalar values: If you know that E is +1.2 moral and -0.6 prudential then it would make sense to choose it over F which is +0.9 moral and -0.6 prudential. If you're ignorant about the relative morality of E and F you might just flip a coin, not realizing that E is the more efficient choice.

In some ways this resembles the consequentialist reasoning behind effective altruism, which explores how give resources to others in a way that most effectively benefits those others. However ethical efficiency is more general, since it encompasses all forms of moral tradeoff including free-riding vs. contributing one's share, lying vs. truth-telling, courageously taking a risk vs. playing it safe, and so on. Also, despite having mathematical features of the sort generally associated with the consequentialist's love of calculations, one needn't be a consequentialist to think this way. One could also reason in terms of tradeoffs in strengths and weaknesses of character (I'm lazy in this, but I make up for it by being courageous about that) or the efficient execution of deontological imperfect duties. Most of us do, I suspect, to some extent weigh up moral and prudiential tradeoffs, as suggested by the phenomena of moral self-licensing (feeling freer to do a bad thing after having done a good thing) and moral cleansing (feeling compelled to do something good after having done something bad).

If all of this is right, then one advantage of discovering moral truths is discovering more efficient ways to achieve your mediocre moral targets with the minimum of self-sacrifice. That is one, perhaps somewhat peculiar, reason to study ethics.

Being ethical in today's world is probably low on most people's lists though most people would desist from the too overtly unethical.

ReplyDeleteAny account of the ethical must include 'appearing ethical' and what motivates people in real life situations.

I'm not so sure ethical behavior easily is separated from real world considerations- which in a way is obvious since ethics is designed to manage our selfishness and so on.

Still it is not something people think about until someone's rights are violated or they have a dilemma or a crime is committed.

I doubt ethical theories have any real autonomy, sadly, so your project is misconceived

I really enjoyed this, thank you for writing it! It occurs to me that for similar reasons, if the person is incorrect about what they do or don't like, then they can improve their tradeoff efficiency by learning more about their own preferences.

ReplyDeleteHi Eric:

ReplyDeleteI gave your article a closer look and will try to address directly your points after an even closer look.

I'd say reframing ethics as something other than ethics might help

Ethics is like a healthy food people don't really want to eat.

Think of it when possible not as a technical problem but as a marketing or motivational problem

There was a time when people did want to do and be good, because of God or because the so called right path was spelled out positively in their culture's tradition: like Spartiates or Orthodox Jews

Thanks for the comments, folks:

ReplyDeleteOwen: Yes, I agree. I left that out of the model for simplicity, but it would be structurally parallel.

Howard: I guess I disagree! I think people do want to be ethical. They just don't (usually) want to sacrifice more for ethical goodness than they see their peers doing. For example, I am impressed how few students appear to cheat on the final exams in my big lower division classes, even though there are ways that they could do so that would trigger suspicion but which we wouldn't be able to prove. I think they see other students being honest and they want to be honest too. Similarly, I think professors want to do right by their colleagues and their students -- not always and not at all costs, but generally so, and often this involves some self-sacrifice and doing some unpleasant tasks with little external reward.

But you said elsewhere that behavior is the ultimate test of belief. How do you justify your conclusion?

ReplyDeleteGood point though on some level. I don't suppose people are bad; but people at the very least worry more about how they are perceived, or about assuring their position or desires are not jeopardized. Or are passively obedient to authority

Psychological and situational variables are confounded with ethics.

Perhaps people on some level want to be ethical, but it's not their primary concern and they're not good at it.

There are other things they want more

I think this is one situation where college students have a different experience than the so called real world: school has defined rules and it centers around their well being and it is simple to play by the rules and straightforward to succeed if not always easy

Despite all their issues they don't face a hostile or indifferent environment that does not affirm their humanity as in the so called real world

Dear Professor

ReplyDeletePeople differently placed in life would settle our differences in different ways.

Not to be sociological, but the kind of ethics and the very idea of ethics have a wide disparity depending on who you ask.

I have a wider set of experiences than most people- not quite Odysseus but I've been exposed to different classes of society-

I told a senior librarian your argument and he and he is a decent person (as opposed to street, see: Code of the street) and very smart, smarter than me, and he said he had a bridge and a tunnel to sell you.

Perhaps someone who was a substitute teacher in a city High School would have a different idea of ethics than a college professor

I think ethics in some ways is indispensable but in some ways a luxury- and it depends on context and is not necessarily universal

Sadly, I have to say I agree with Howard. It just doesn't seem that morality is something that plays a factor in most people's decision making most of the time. I would say it very rarely does, in fact. I think WHEN ASKED most people will say they aim for moral mediocrity, or will engage in some sort of post hoc rationalization in retrospect, but moral considerations don't seem guiding in the majority of situations for most people.

ReplyDeleteTo your college students not cheating more point: my interpretation is that most students don't cheat because most other students don't cheat. Full stop. No need to bring thoughts of morality into it at all. With regard to morality, most students aren't aiming at anything.

If you aren't in the habit of thinking about your actions in terms of their moral impact, and then making decisions based on the moral considerations, you simply won't generally do it. Which is why I think it is so important that we include things that encourage and cultivate ethical or ethical-like thinking in education. It gets people in the habit of engaging in the sorts of thinking important for ethical consideration ( i.e. the moral importance of narrative! :D ).

I find this an odd discussion. It sounds like a class in economics. It seems as if being “good” is some sort of commodity that we purchase with our actions. It also seems as if this commodity then performs the functions of acceptance and validation within our community—like a house or a new car—which should be at least minimally impressive to our neighbors. For example, as Prof Eric Schwitzgebel says “one advantage of discovering moral truths is discovering more efficient ways to achieve your mediocre moral targets with the minimum of self-sacrifice.” In response to a comment he says, people want to be ethical, “they just don’t (usually) want to sacrifice more for ethical goodness than they see their peers doing.” What are we sacrificing? Does doing the right thing come with a price tag? It’s like trying to figure out how much of the traffic code (stopping at red lights, yielding to pedestrians, etc.) I can avoid yet still be considered a good driver. Is ethical action like adhering to the traffic code? Very strange. Is that what you all really think of as ethics?

ReplyDeleteThanks for the question...'What are we sacrificing'...

ReplyDeleteAre sacrifice and self fundamental to ethics morality value...

I am never sure if dualism and monism theories want to experience understanding...

Actually Matti, that is about what I think of as “ethics” or “moral notions”. In many ways I’m certainly not typical however, and certainly not here. Though professor S. may have written this post, I think he does cheer for your perspective to hopefully prevail some day. Unlike him I doubt that I’ll ever agree to the existence of “moral truths” for example. The problem is that he’s generally run into opposing evidence.

ReplyDeleteEven though science is able to study non human stuff in “hard” ways, I suspect that psychology largely remains “soft” because the social tool of morality has not yet permitted science to reduce human psychological function back to basic components. We can of course reduce plants down to basic components without getting morally judgmental for example, though reducing ourselves this way seems too sticky — reality shouldn’t always conform with what we’re naturally encouraged to believe about ourselves.

For example in my first comment on the “Longtermism” post just before this one, I did pondered saying that if we were to figure out how to make ourselves feel millions of times better than normal, as well as build machines that could take care of us in ways that we thus wouldn’t be, then such an end should be our destiny. But I also realized that this conclusion should be too repugnant and ultimately immoral for many to tolerate. So on the hope of fostering objective consideration I instead presented some basic psychology for a creature on another planet that logically ought to end up like that. Then with the model in place I could simply say “us too”.

Well, good luck with your reduction project! I hope you can find that moral sweet spot that produces the biggest bang for your moral buck. Here’s hoping also you can crack that knotty conundrum of why people who have studied ethics don’t seem behave better. Similarly, I have put years of reading and study into music theory, yet I’m still an absolute klutz on the piano. I can’t seem to figure out why!

ReplyDelete