Though I'm not a vegetarian, one of my research interests is the moral psychology of vegetarianism. Last weekend, when I was in Princeton giving a talk on robot rights, a vegetarian apologized to me for being vegetarian.

As a meat-eater, I find it's not unusual for vegetarians to apologize to me. Maybe this wouldn't be so notable if their vegetarianism inconvenienced me in any way, but often it does not. In Princeton, we were both in line for a catering spread that had both meat and vegetarian options. I was in no obvious way wronged, harmed, or inconvenienced. So what is going on?Here's my theory.

Generally speaking, I believe that people aim to be morally mediocre. That is, rather than aiming to be morally good (or not morally bad) by absolute standards, most people aim to be about as morally good as their peers -- not especially better, not especially worse. People might not conceptualize themselves as aiming for mediocrity. Often, they concoct post-hoc rationalizations to justify their choices. But their choices implicitly reveal their moral target. Systematically, people avoid being among the worst of their peers while refusing the pay the costs of being among the best. For example, they don't want to be the one jerk who messes up a clean environment; but they also don't want to be the one sucker who puts in the effort to keep things clean if others aren't also doing so. (See my notes on the game of jerk and sucker.)

Now if people do in fact aim to be about as morally good as their peers, we can expect that under certain conditions they don't want their peers to improve their moral behavior. Under what conditions? Under the conditions that your peers' self-improvement benefits you less than the raising of the moral bar costs you.

Let's say that your friends all become nicer to each other. This isn't so bad. You benefit from being in a circle of nice people. Needing to become a bit nicer yourself might be a reasonable cost to pay for that benefit.

But if your friends start becoming vegetarians, you accrue the moral costs without the benefits. The moral bar is raised for you, implicitly, at least a little bit; but the benefits go to non-human animals, if they go anywhere. You now either have to think a bit worse of yourself relative to your peers or you have to start changing your behavior. How annoying! No wonder vegetarians are moved to apologize. (To be clear, I'm not saying we should be annoyed by this, just that my theory predicts that we will be annoyed.)

Note that this explanation works especially well for those of us who think it is morally better to avoid eating meat than for those of us who see no moral difference between eating meat and eating vegetarian. If you really see no moral difference (deep down, and not just because of superficial, post-hoc rationalization), then you'll see the morally motivated vegetarian just as morally confused. If they apologize, it would be like someone apologizing to you for acting according to some other mistaken moral principle, such as apologizing for abstinence before marriage. No one needs to apologize to you for that, unless they are harming or inconveniencing you in some way -- for example, because they are dating you and think you'll be disappointed. (Alternatively, they might apologize for the more abstract wrong of seeing you as morally deficient because you follow different principles; but that type of apology looks and feels a little different, I think.)

If this moral mediocrity explanation of vegetarian apology works, it ought to generalize to other cases where friends follow higher moral standards that don't benefit you. Some possible examples: In a circle of high school students who habitually cheat on tests, a friend might apologize for being unwilling to cheat. In a group of people who feel somewhat guilty about taking a short cut through manicured grass, one might decide they want to take the long way, apologizing to the group for the extra time, feeling more guilt than would accompany an ethically neutral reason for delay. On this model, the felt need for the apology would vary with a few predictable parameters: greater need the closer one is to being a peer whose behavior might be compared, greater need the more vivid and compelling the comparison (for example if you are side by side), lesser need the more the moral principle can be seen as idiosyncratic and inapplicable to the other (and thus some apologies of this sort suggest that the principle is idiosyncratic).

Do-gooder derogation is the tendency for people to think badly of people who follow more demanding moral standards. The moral mediocrity hypothesis is one possible explanation for this tendency, predicting among other things that derogation will be greater when the do-gooder is a peer and, perhaps unintuitively, that the derogation will be greater when the moral standard is compelling enough to the derogator that they already feel a little bit bad about not adhering to it.

-------------------------------------------

Related:

The Collusion Toward Moral Mediocrity (Sep 1, 2022)

Aiming for Moral Mediocrity (Res Philosophica, 2019)

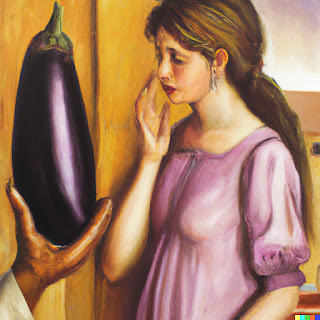

Image: Dall-E 2 "oil painting of a woman apologizing to an eggplant"