According to "longtermism" (as I'll use the term), our thinking should be significantly influenced by our expectations for the billion-plus-year future. In a paper in draft, I argue, to the contrary, that our thinking should be not at all influenced by our expectations for the billion-year-plus future. Every action has so vastly many possible positive and negative future consequences that it's impossible to be justified in expecting that any action currently available to us will have a non-negligible positive impact that far into the future. Last week, I presented my arguments against longtermism to Oxford's Global Priorities Institute, the main academic center of longtermist thinking.

The GPI folks were delightfully welcoming and tolerant of my critiques, and they are collectively nuanced enough in their thinking to already have anticipated the general form of all of my main concerns in various places in print. What became vivid for me in discussion was the extent to which my final negative conclusion about longtermist reasoning depends on a certain meta-epistemic objection -- that is, the idea that our guesses about the good or bad consequences of our actions for the billion-year-plus future are so poorly grounded that we are epistemically better off not even guessing.

The contrary position, seemingly held by several of the audience members at GPI, is that, sure, we should be very epistemically humble when trying to estimate good or bad consequences for the billion-year-plus future -- but still we might find ourselves, after discounting for our likely overconfidence and lack of imagination, modestly weighing up all the uncertainties and still judging that action A really would be better than action B in the billion-plus-year future; and then it's perfectly reasonable to act on this appropriately humble, appropriately discounted judgment.

They are saying, essentially, play the game carefully. I'm saying don't play the game. So why do I think it's better not even to play the game? I see three main reasons.

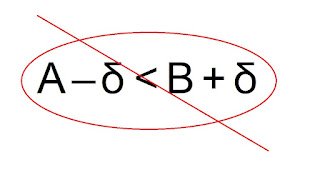

[image of A minus delta < B plus delta, overlaid with a red circle and crossout line]First, longtermist reasoning requires cognitive effort. If the expected benefit of longtermist reasoning is (as I suggest in one estimate in the full-length essay draft) one quadrillionth of a life, it might not be worth a millisecond of cognitive effort to try to get the decision right. One's cognitive resources would be better expended elsewhere.

Now one response to this -- a good response, I think, at least for a certain range of thinkers in a certain range of contexts -- is that reflecting about the very distant future is fun, engaging, mind-opening, and even just intrinsically worthwhile. I certainly wouldn't want to shame anyone just for thinking about it! (Among other things, I'm a fan of science fiction.) But I do think we should bear the cost argument in mind to the extent our aim is the efficient use of cognitive labor for improving the world. It's likely that there are many more productive topics to throw your cognitive energies at, if you want to positively influence the future -- including, I suspect, just being more thoughtful about the well-being of people in your immediate neighborhood.

Second, longtermist reasoning adds noise and error into the decision-making process. Suppose that when considering the consequences of action A vs. action B for "only" the next thousand years, you come to the conclusion that action A would be better. But then, upon further reflection, you conclude -- cautiously, with substantial epistemic discounting -- that looking over the full extent of the next billion-plus years, B in fact has better expected consequences. The play carefully and don't play approaches now yield different verdicts about what you should do. Play carefully says B. Don't play says A. Which is likely to be the better policy, as a general matter? Which is likely to lead to better decisions and consequences overall, across time?

Let's start with an unflattering analogy. I'll temper it in a minute. Suppose that you favor action A over action B on ordinary evidential grounds, but then after summing all those up, you make the further move of consulting a horoscope. Assuming horoscopes have zero evidential value, the horoscope adds only noise and error to the process. If the horoscope "confirms" A, then your decision is the same as it would have been. If the horoscope ends up tilting you toward B, then it has led you away from your best estimate. It's better, of course, for the horoscope to play no role.

Now what if the horoscope -- or, to put it more neutrally, Process X -- adds a tiny bit of evidential value -- say, one trillionth of the value of a happy human life? That is, suppose that if the Process X says "Action B will increase good outcomes by trillions of lives". You then discount the output of Process X a lot -- maybe by 24 orders of magnitude. After this discounting of its evidentiary value, you consequently increase your estimate of the value of Action B by one trillionth of a life. In that case, almost no practical decisions which involve the complex weighing up of competing costs and benefits should be such that the tiny Process X difference is sufficient to rationally shift you from choosing A to choosing B. You would probably be better off thinking a bit more carefully about other pros and cons. Furthermore, I suspect that -- as a contingent matter of human psychology -- it will be very difficult to give Process X only the tiny, tiny weight it deserves. Once you've paid the cognitive costs of thinking through Process X, that factor will loom salient for you and be more than a minuscule influence on your reasoning. As a result, incorporating Process X into your reasoning will add noise and error, of a similar sort to the pure horoscope case, even if it has some tiny predictive value.

Third, longtermist reasoning might have negative effects on other aspects of one’s cognitive life, for example, by encouraging inegalitarian or authoritarian fantasies, or a harmful neo-liberal quantification of goods, or self-indulgent rationalization, or a style of consequentialist thinking that undervalues social relationships or already suffering people. This is of course highly speculative and contingent both on the contingent psychology of the longtermists in question and the value or disvalue of, for example, "neo-liberal quantification of goods". But in general cognitive complexity is fertile soil for cognitive vice. Perhaps rationalization is most straightforward version of this objection: If you are emotionally attracted to Action B -- if you want it to be the case that B is the best choice -- and if billion-year-plus thinking seems to favor Action B, it's plausible that you'll give that fact more than the minuscule-upon-minuscule weight it deserves (if my other arguments concerning longtermism are correct).

Now it might be the case that longtermist reasoning also has positive effects on the longtermist thinker -- for example, by encouraging sympathy for distant others, or by fruitfully encouraging more two-hundred-year thinking, or by encouraging a flexible openness of mind. This is, I think, pretty hard to know; but longtermists' self-evaluations and peer evaluations are probably not a reliable source here.

[Thanks to all the GPI folks for comments and discussion, especially Christian Tarsney.]

4 comments:

The psychology of movement is founded in neurology's appreciation of semantics...

Thus providing us with something more to do than just sense-we began to invent words...

...for learning knowledge and understanding, of ourselves as what we are-what we want...

We are not just a pile of bones from the past for paleontologists and globalist alike...

...I am here now and then too, learning with others to stay here...

As long as I can, what is up to me...

If I understand this, even partially, longtermism suggests we can control---even mould---our destiny, through sheer force of determination and will. This is true to some extent. But it is not *money in the bank*. If it WERE patently true, there should be a lot more truly content people walking around! My conclusion, one anyway, is a longtermist view is contingent on things "going right". Obviously, that does not always, or in all ways happen, determination and will, notwithstanding.

Yes Paul agreed- how about the scenario of a supercomputer as a benevolent God?

Perhaps we can create a supercomputer that would not only guide humanity but combat malicious csupercomputers?

Arnold: todays headline..."Google DeepMind Shifts From Research Lab to AI Product Factory" vs longtermism...

Gemini: 'Google DeepMind's is a AI research lab...it seems to be prioritizing creating commercial AI products over pure research. This could mean faster development of practical AI applications but potentially less focus on fundamental breakthroughs.'

Arnold: How about 'AI Product Factory' for Seven Generation Substantiveness'; toward 100% resource and recycling for our planet...

Gemini: "Seven Generation Substantiveness: This refers to a philosophy rooted in some Indigenous cultures, where decisions consider the impact on seven generations into the future. The AI products from this factory would be designed with this long-term perspective in mind."

Arnold: First AI product: a AI Philosophy for seven generations of substantiveness...

Gemini?: LLMs are watching, listening and learning...

Post a Comment