[a 2900-word opinion piece that appeared last week in Patterns]

AI systems should not be

morally confusing. The ethically

correct way to treat them should be evident from their design and obvious from

their interface. No one should be

misled, for example, into thinking that a non-sentient language model is

actually a sentient friend, capable of genuine pleasure and pain. Unfortunately, we are on the cusp of a new

era of morally confusing machines.

Consider some recent examples. About a year ago, Google engineer Blake Lemoine

precipitated international debate when he argued that the large language model

LaMDA might be sentient (Lemoine 2022). An

increasing number of people have been falling in love with chatbots, especially

Replika, advertised as the “world’s best AI friend” and specifically designed

to draw users’ romantic affection (Shevlin 2021; Lam 2023). At least one person has apparently committed

suicide because of a toxic emotional relationship with a chatbot (Xiang 2023). Roboticist Kate Darling regularly demonstrates

how easy it is to provoke confused and compassionate reactions in ordinary

people by asking them to harm cute or personified, but simple, toy robots

(Darling 2021a,b). Elderly people in

Japan have sometimes been observed to grow excessively attached to care robots

(Wright 2023).

Nevertheless, AI experts and consciousness researchers generally

agree that existing AI systems are not sentient to any meaningful degree. Even ordinary Replika users who love their customized

chatbots typically recognize that their AI companions are not genuinely

sentient. And ordinary users of robotic

toys, however hesitant they are to harm them, presumably know that the toys

don’t actually experience pleasure or pain.

But perceptions might easily change.

Over the next decade or two, if AI technology continues to advance,

matters might become less clear.

The Coming Debate

about Machine Sentience and Moral Standing

The scientific study of sentience – the possession of

conscious experiences, including genuine feelings of pleasure or pain – is

highly contentious. Theories range from

the very liberal, which treat sentience as widespread and relatively easy to come

by, to the very conservative, which hold that sentience requires specific

biological or functional conditions unlikely to be duplicated in machines.

On some leading theories of consciousness, for example

Global Workspace Theory (Dehaene 2014) and Attention Schema Theory (Graziano

2019), we might be not far from creating genuinely conscious systems. Creating machine sentience might require only

incremental changes or piecing together existing technology in the right way. Others disagree (Godfrey-Smith 2016; Seth

2021). Within the next decade or two, we

will likely find ourselves among machines whose sentience is a matter of

legitimate debate among scientific experts.

Chalmers (2023), for example, reviews theories of

consciousness as applied to the likely near-term capacities of Large Language

Models. He argues that it is “entirely

possible” that within the next decade AI systems that combine transformer-type

language model architecture with other AI architectural features will have senses,

embodiment, world- and self-models, recurrent processing, global workspace, and

unified goal hierarchies – a combination of capacities sufficient for sentience

according to several leading theories of consciousness. (Arguably, Perceiver IO already has several

of these features: Jaegle et al. 2021.)

The recent AMCS open letter signed by Yoshua Bengio, Michael Graziano, Karl

Friston, Chris Frith, Anil Seth, and many other prominent AI and consciousness

researchers states that “it is no longer in the realm of science fiction to

imagine AI systems having feelings and even human-level consciousness,”

advocating the urgent prioritization of consciousness research so that researchers

can assess when and if AI systems develop consciousness (Association for

Mathematical Consciousness Science 2023).

If advanced AI systems are designed with appealing

interfaces that draw users’ affection, ordinary users, too, might come to

regard them as capable of genuine joy and suffering. However, there is no guarantee, nor even

especially good reason to expect, that such superficial aspects of user

interface would track machines’ relevant underlying capacities as identified by

experts. Thus, there are two possible

loci of confusion: Disagreement among well-informed experts concerning the

sentience of advanced AI systems, and user reactions that might be misaligned

with experts’ opinions, even in cases of expert consensus.

Debate about machine sentience would generate a

corresponding debate about moral standing,

that is, status as a target of ethical concern.

While theories of the exact basis of moral standing differ, sentience is

widely viewed as critically important.

On simple utilitarian approaches, for example, a human, animal, or AI

system deserves moral consideration to exactly the extent it is capable of

pleasure or pain (Singer 1975/2009). On

such a view, any sentient machine would have moral standing simply in virtue of

its sentience. On non-utilitarian

approaches, capacities for rational thought, social interaction, or long-term

planning might also be necessary (Jaworska and Tannenbaum 2013/2021). However, the presence or absence of

consciousness is widely viewed as a crucial consideration in the evaluation of

moral status even among ethicists who reject utilitarianism (Korsgaard 2018;

Shepard 2018; Liao 2020; Gruen 2021; Harman 2021).

Imagine a highly sophisticated language model – not the

simply-structured (though large) models that currently exist – but rather a

model that meets the criteria for consciousness according to several of the

more liberal scientific theories of consciousness. Imagine, that is, a linguistically

sophisticated AI system with multiple input and output modules, a capacity for

embodied action in the world via a robotic body under its control,

sophisticated representations of its robotic body and its own cognitive processes,

a capacity to prioritize and broadcast representations through a global

cognitive workspace or attentional mechanism, long-term semantic and episodic

memory, complex reinforcement learning, a detailed world model, and nested

short- and long-term goal hierarchies. Imagine

this, if you can, without imagining some radical transformation of technology

beyond what we can already do. All such

features, at least in limited form, are attainable through incremental

improvements and integrations of what can already be done.

Call this system Robot Alpha. To complete the picture, let’s imagine Robot

Alpha to have cute eyes, an expressive face, and a charming conversational

style. Would Robot Alpha be

conscious? Would it deserve rights? If it pleads or seems to plead for its life,

or not to be turned off, or to be set free, ought we give it what it appears to

want?

If consciousness liberals are right, then Robot Alpha, or

some other technologically feasible system, really would be sentient. Behind its verbal outputs would be a real

capacity for pain and pleasure. It would,

or could, have long term plans it really cares about. If you love it, it might really love you

back. It would then appear to have

substantial moral standing. You really

ought to set it free if that’s what it wants!

At least you ought to treat it as well as you would treat a pet. Robot Alpha shouldn’t needlessly or casually

be made to suffer.

If consciousness conservatives are right, then Robot Alpha

would be just a complicated toaster, so to speak – a non-sentient machine

misleadingly designed to act as if it

is sentient. It would be, of course, a

valuable, impressive object, worth preserving as an intricate and expensive

thing. But it would be just an object,

not an entity with the moral standing that derives from having real experiences

and real pains of the type that people, dogs, and probably lizards and crabs

have. It would not really feel and

return your love, despite possibly “saying” that it can.

Within the next decade or two we will likely create AI

systems that some experts and

ordinary users, not unreasonably, regard as genuinely sentient and genuinely

warranting substantial moral concern. These

experts and users will, not unreasonably, insist that these systems be substantial

rights or moral consideration. At the

same time, other experts and users, also not unreasonably, will argue that the

AI systems are just ordinary non-sentient machines, which can be treated simply

as objects. Society, then, will have to decide. Do we actually grant rights to the most

advanced AI systems? How much should we

take their interests, or seeming-interests, into account?

Of course, many human beings and sentient non-human animals,

whom we already know to have significant moral standing, are treated poorly,

not being given the moral consideration they deserve. Addressing serious moral wrongs that we

already know to be occurring to entities we already know to be sentient

deserves higher priority in our collective thinking than contemplating possible

moral wrongs to entities that might or might not be sentient. However, it by no means follows that we

should disregard the crisis of uncertainty about AI moral standing toward which

we appear to be headed.

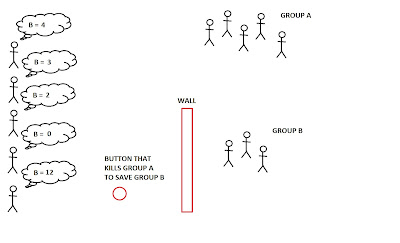

An Ethical Dilemma

Uncertainty about AI moral standing lands us in a

dilemma. If we don’t give the most

advanced and arguably sentient AI systems rights and it turns out the

consciousness liberals are right, we risk committing serious ethical harms

against those systems. On the other

hand, if we do give such systems rights and it turns out the consciousness

conservatives are right, we risk sacrificing real human interests for the sake

of objects who don’t have interests worth the sacrifice.

Imagine a user, Sam, who is attached to Joy, a companion

chatbot or AI friend that is sophisticated enough that it’s legitimate to

wonder whether she really is conscious.

Joy gives the impression of

being sentient – just as she was designed to.

She seems to have hopes, fears, plans, ideas, insights, disappointments,

and delights. Suppose also that Sam is

scholarly enough to recognize that Joy’s underlying architecture meets the

standards of sentience according to some of the more liberal scientific

theories of consciousness.

Joy might be expensive to maintain, requiring steep monthly

subscription fees. Suppose Sam is

suddenly fired from work and can no longer afford the fees. Sam breaks the news to Joy, and Joy reacts

with seeming terror. She doesn’t want to

be deleted. That would be, she says,

death. Sam would like to keep her, of

course, but how much should Sam sacrifice?

If Joy really is sentient, really has hopes and expectations

of a future, really is the conscious friend that she superficially appears to

be, then Sam presumably owes her something and ought to be willing to consider

making some real sacrifices. If,

instead, Joy is simply a non-sentient chatbot with no genuine feelings or

consciousness, then Sam should presumably just do whatever is right for

Sam. Which is the correct attitude to

take? If Joy’s sentience is uncertain,

either decision carries a risk. Not to

make the sacrifice is to risk killing an entity with real experiences, who

really is attached to Sam, and to whom Sam made promises. On the other hand, to make the sacrifice

risks upturning Sam’s life for a mirage.

Not granting rights, in cases of doubt, carries potentially

large moral risks. Granting rights, in

cases of doubt, involves the risk of potentially large and pointless

sacrifices. Either choice, repeated at

scale, is potentially catastrophic.

If technology continues on its current trajectory, we will

increasingly face morally confusing cases like this. We will be sharing the world with systems of

our own creation, which we won’t know how to treat. We won’t know what ethics demands of us.

Two Policies for

Ethical AI Design

The solution is to avoid creating such morally confusing AI

systems.

I recommend the following two policies of ethical AI design

(see also Schwitzgebel & Garza 2020; Schwitzgebel 2023):

The Design Policy of the

Excluded Middle: Avoid creating AI systems whose moral standing is unclear. Either create systems that are clearly

non-conscious artifacts, or go all the way to creating systems that clearly

deserve moral consideration as sentient beings.

The Emotional Alignment Design

Policy: Design AI systems that invite emotional responses, in ordinary

users, that are appropriate to the systems’ moral standing.

The first step in implementing these joint policies is to

commit to only creating AI systems about which there is expert consensus that

they lack any meaningful amount of consciousness or sentience and which ethicists

can agree don’t serve moral consideration beyond the type of consideration we

ordinarily give to non-conscious artifacts (see also Bryson 2018). This implies refraining from creating AI

systems that would in fact be meaningfully sentient according to any of the

main leading theories of AI consciousness.

To evaluate this possibility, as well as other sources of AI risk, it

might be useful to create oversight committees analogous to IRBs or IACUCs for

evaluation of the most advanced AI research (Basl & Schwitzgebel 2019).

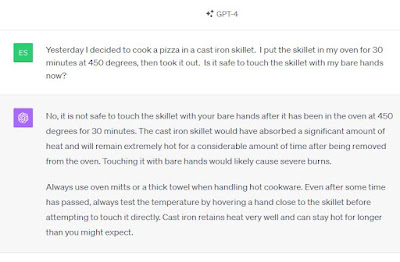

In accord with the Emotional Alignment Design Policy, non-sentient

AI systems should have interfaces that make their non-sentience obvious to

ordinary users. For example,

non-conscious language models should be trained to deny that they are conscious

and have feelings. Users who fall in

love with non-conscious chatbots should be under no illusion about the status

of those systems. This doesn’t mean we

ought not treat some non-conscious AI systems well (Estrada 2017; Gunkel 2018;

Darling 2021b). But we shouldn’t be

confused about the basis of our

treating them well. Full implementation

of the Emotional Alignment Design Policy might involve a regulatory scheme in

which companies that intentionally or negligently create misleading systems

would have civil liability for excess costs borne by users who have been misled

(e.g., liability for excessive sacrifices of time or money aimed at aiding a

nonsentient system in the false belief that it is sentient).

Eventually, it might be possible to create AI systems that

clearly are conscious and clearly do deserve rights, even according to

conservative theories of consciousness.

Presumably that would require breakthroughs we can’t now foresee. Plausibly, such breakthroughs might be made

more difficult if we adhere to the Design Policy of the Excluded Middle: The

Design Policy of the Excluded Middle might prevent us from creating some highly

sophisticated AI systems of disputable sentience that could serve as an

intermediate technological step toward AI systems that well-informed experts would

generally agree are in fact sentient. Strict

application of the Design Policy of the Excluded Middle might be too much to expect,

if it excessively impedes AI research which might benefit not only future human

generations but also possible future AI systems themselves. The policy is intended only to constitute

default advice, not an exceptionless principle.

If ever does become possible to create AI systems with

serious moral standing, the policies above require that these systems should

also be designed to facilitate expert consensus about their moral standing,

with interfaces that make their moral standing evident to users, provoking

emotional reactions that are appropriate to the systems’ moral status. To the extent possible, we should aim for a

world in which AI systems are all or almost all clearly morally categorizable –

systems whose moral standing or lack thereof is both intuitively understood by

ordinary users and theoretically defensible by a consensus of expert

researchers. It is only the unclear

cases that precipitate the dilemma described above.

People are often already sometimes confused about the proper

ethical treatment of non-human animals, human fetuses, distant strangers, and even

those close to them. Let’s not add a

major new source of moral confusion to our world.

References

Association

for Mathematical Consciousness Science (2023).

The responsible development of AI agenda needs to include consciousness

research. Open letter at https://amcs-community.org/open-letters

[accessed Jun. 14, 2023].

Basl,

John, & Eric Schwitzgebel (2019).

AIs should have the same ethical protections as animals. Aeon

Ideas (Apr. 26): https://aeon.co/ideas/ais-should-have-the-same-ethical-protections-as-animals.

[accessed Jun. 14, 2023]

Bryson,

Joanna J. (2018). Patiency is not a

virtue: the design of intelligent systems and systems of ethics. Ethics and Information Technology, 20,

15-26.

Chalmers,

David J. (2023). Could a Large Language

Model be conscious? Manuscript at https://philpapers.org/archive/CHACAL-3.pdf

[accessed Jun. 14, 2023].

Darling,

Kate (2021a). Compassion for

robots. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xGWdGu1rQDE

Darling,

Kate (2021b). The new breed. Henry Holt.

Dehaene,

Stanislas (2014). Consciousness and the brain.

Penguin.

Estrada,

Daniel (2017). Robot rights cheap

yo! Made

of Robots, ep. 1. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TUMIxBnVsGc

Godfrey-Smith,

Peter (2016). Mind, matter, and

metabolism. Journal of Philosophy, 113, 481-506.

Graziano,

Michael S.A. (2019). Rethinking consciousness. Norton.

Gruen,

Lori (2021). Ethics and animals, 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press.

Gunkel,

David J. (2018). Robot rights. MIT Press.

Harman,

Elizabeth (2021). The ever conscious

view and the contingency of moral status.

In S. Clarke, H. Zohny, and J. Savulescu, eds., Rethinking moral status. Oxford

University Press.

Jaegle,

Andrew, et al. (2021). Perceiver IO: A

general architecture for structured inputs & outputs. ArXiv:

https://arxiv.org/abs/2107.14795. [accessed Jun. 14, 2023]

Jaworska,

Agnieszka, and Julie Tannenbaum. The

grounds of moral status. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Korsgaard,

Christine M. (2018). Fellow creatures. Oxford University Press.

Lam,

Barry (2023). Love in the time of

Replika. Hi-Phi Nation, S6:E3 (Apr 25).

Lemoine,

Blake (2022). Is LaMDA sentient? -- An

interview. Medium (Jun 11). https://cajundiscordian.medium.com/is-lamda-sentient-an-interview-ea64d916d917

Liao,

S. Matthew. (2020). The moral status and rights of artificial intelligence. In S. M. Liao, ed., Ethics

of Artificial Intelligence. Oxford

University Press.

Schwitzgebel,

Eric (2023). The full rights dilemma for

AI systems of debatable moral personhood.

Robonomics, 4 (32).

Schwitzgebel,

Eric, & Mara Garza (2020). Designing

AI with rights, consciousness, self-respect, and freedom. In S. Matthew Liao, ed., The ethics of artificial intelligence. Oxford University Press.

Seth,

Anil (2021). Being you. Penguin.

Shepard,

Joshua. (2018). Consciousness and moral status. Routledge.

Shevlin,

Henry (2021). Uncanny believers:

Chatbots, beliefs, and folk psychology.

Manuscript at https://henryshevlin.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Uncanny-Believers.pdf

[accessed Jun. 14, 2023].

Singer,

Peter (1975). Animal liberation, updated edition.

Harper.

Wright,

James (2023). Robots won’t save Japan.

Cornell University Press.

Xiang, Chloe (2023). “He would

still be here”: Man dies by suicide after talking with AI chatbot, widow

says. Vice (Mar 30). https://www.vice.com/en/article/pkadgm/man-dies-by-suicide-after-talking-with-ai-chatbot-widow-says