I favor a "dispositional" approach to belief, according to which to believe something is nothing more or less than to have a certain suite dispositions. To believe there is beer in the fridge, for example, is nothing more than to be disposed to go to the fridge if you want a beer, to be ready to assert that there is beer in the fridge, to feel surprise should you open the fridge and find no beer, to be ready conclude that there is beer within 15 feet of the kitchen table should the question arise, and so on -- all imperfectly, approximately, and in normal conditions absent countervailing pressures. Crucially, on dispositional accounts it doesn't matter what interior architectures underwrite the dispositions. In principle, you could have a head full of undifferentiated pudding -- or even an immaterial soul! As long as it's still the case that (somehow, perhaps in violation of the laws of nature) you stably have the full suite of relevant dispositions, you believe.

One standard objection to dispositionalist accounts (e.g. by Jerry Fodor and Quilty-Dunn and Mandelbaum) is this. Beliefs are causes. Your belief that there is beer in the fridge causes you to go to the fridge when you want a beer. But dispositions don't cause anything; they're the wrong ontological type.

A large, fussy metaphysical literature addresses whether dispositions can be causes (brief summary here). I'd rather not take a stand. To get a sense of the issue, consider a simple dispositional property like fragility. To be fragile is to be disposed to break when struck (well, it's more complicated than that, but just pretend). Why did my glass coffee mug break yesterday morning when I drove off with it still on the roof of my car and it fell to the road? (Yes, that happened.) Because it was fragile, yes. But the cause of the breaking, one might think, was not its dispositional fragility. Rather, it was a specific event at a specific time -- the event of the mug's striking the pavement. Cause and effect are events, analytically distinct from each other. But the fragility and the breaking are not analytically distinct, since to be fragile just is to be disposed to break. To say something is fragile is to say that certain types of causes will have certain types of effects. It's a higher level of description, the thinking goes.

Returning to belief, then, the objector argues: If to believe there is beer in the fridge just is to be disposed to go to the fridge if one wants a beer, then the belief doesn't cause the going. Rather, it is the general standing tendency to go, under certain conditions.

Now maybe this argument is all wrong and dispositions can be causes (or maybe the event of having a particular dispositional property can be a partial cause), but since I don't want to commit on the issue, I need to make sense of an alternative view.

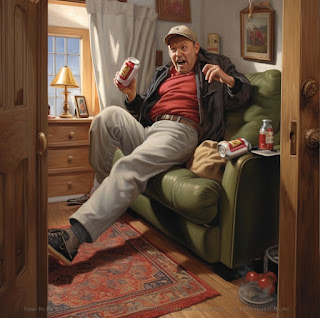

[Midjourney rendition of getting off the couch to go get a beer from the fridge, happy]On the alternative view I favor, dispositional properties aren't causes, but they figure in causal explanations -- and that's all we really want or need them to do. It is not obvious (contra Fodor, Quilty-Dunn, and Mandelbaum) that we need beliefs to do more than that, either in our everyday thinking about belief or in cognitive science.

Consider the personality trait of extraversion. Plausibly, personality traits are dispositional: To be an extravert is nothing more or less than to be disposed to enjoy the company of crowds of people, to take the lead in social situations, to seek out new social connections, etc. (imperfectly, approximately, in normal conditions absent countervailing pressures). Even people who don't like dispositionalism about belief are often ready to accept that personality traits are dispositional.

If we then also accept that dispositions can't be causes, we have to say that being extraverted didn't cause Nancy to say yes to the party invitation. On this view, to be extraverted just is the standing general tendency to do things like say yes when invited to parties. But still, of course, we can appeal to Nancy's extraversion to explain why she said yes. If Jonathan asks Emily why Nancy agreed to go, Emily might say that Nancy is an extravert. That's a perfectly fine, if vague and incomplete, explanation -- a different explanation than, for example, that she was looking for a new romantic partner or wanted an excuse to get out of the house.

Clearly, people sometimes go to the fridge because they believe that's where the beer is. But this can be an explanation of the same general structure as the explanation that Nancy went to the party because she's an extravert. Anyone who denies that dispositions are causes needs a good account of how dispositional personality traits (and fragility) can help explain why things happen. Maybe it's a type of "unification explanation" (explaining by showing how a specific event fits into a larger pattern), or maybe it's explanation by appeal to a background condition that is necessary for the cause (the striking, the invitation, the beer desire) to have its effect (the breaking, the party attending, the trip to the fridge). However it goes, personality trait explanation works without being vacuous.

Whatever explanatory story works for dispositional personality traits should work for belief. If ordinary usage or cognitive science requires that beliefs be causes in a more robust metaphysical sense than that, further argument will be required than I have seen supplied by those who object to dispositional accounts of belief on causal grounds.

Obviously, it's sometimes true that to say "I went to the fridge because I believed that's where the beer was" and "because Linda strongly believed that P, when she learned that P implies Q, she concluded Q". Fortunately, the dispositionalist about belief needn't deny such obvious truths. But it is not obvious that beliefs cause behavior in whatever specific sense of "cause" a metaphysician might be employing if they deny that fragility causes glasses to break and extraversion causes people to attend parties.

14 comments:

My guess is, Eric, you doubt there is a mind, or see it as something that doesn't hold beliefs

My guess about this (not having thought too much about what dispositions are) is that the relationship between the disposition and the thing that is causal is the same as the relationship between the role and the realizer for the functionalist, which fits with this. I've seen this sort of thing discussed most in biological contexts, where people want to say that it's not correct to say "this creature reproduced more than that one because it was fitter", but better to say "this creature reproduced more than that one because it had a longer neck, and thus in this context, having a longer neck is a way of being fitter". Maybe one creature got up and went to the fridge because it had "there is beer in the fridge" written in the belief box, and its belief box is hooked up to the desire box in such a way that they tend to produce this motion; maybe the other creature got up and went to the fridge because its hydraulic sacs are so constituted; and this causal description is what it means for the belief box to count as "belief" for the one and the hydraulic sacs to count as "belief" for the other.

So believing there's beer in the fridge is in part being disposed to open it if you want a beer. And I imagine you'll hold that wanting a beer is in part being disposed to open the fridge if you believe there's beer in it. Suppose your action/surprise/etc. dispositions at the moment check all the other boxes for having that belief and for having that desire, and suppose you in fact now open the fridge. Is this evidence that you *do* have that final disposition needed to count as having the belief and the desire? It seems consistent with that, of course, but why isn't it also consistent with your having neither or with your having one but not the other state (so that the open-the-fridge prediction that *would* be entailed by your having both states is simply not entailed by states you are in, and no false prediction is entailed either)?

This is a version of an old vicious-circularity worry about philosophical/logical behaviorism -- one that functionalism was supposed to have solved -- so I imagine you have a way around it.

Very well put!

Thanks for the comments, folks!

Howard: I wouldn’t put it that way myself.

Kenny: Yes, maybe — though there’s a threat of vacuousness to “the creature reproduced more because it was fitter” if read in a certain way, which I don’t think we see when explaining particular actions by appeal to personality or belief.

Anon: Right! There’s a problem there if the aim is to reductionistically purge all mental vocabulary. One answer is Lewisian Ramsification, which needn’t be only in terms of causal properties. Another is to hold phenomenal dispositions fixed (the feeling of surprise will be different with the beer belief than with others). Another is to hold desire fixed when thinking about belief and vice versa rather than aim for wholesale reduction (Neurath’s boat).

When fussiness metaphysics moves teleology and foundations of philosophy...

Then study of being-in-between origins and original may occur..

...allowing the fragility of categories to find their place...

Where new beginnings can be found constant, says Mr. Aristotle...

...thanks for the great reads...

I consider debate regarding dispositionalism versus representationalism far too platonic. It’s as if there’s some sort of truth to discover behind the humanly fabricated term “belief”. Furthermore I counter this perspective by means of my first principle of epistemology. It states that we shouldn’t consider any term to have a true or false definition, but rather more and less useful ones in a given context. William of Occam essentially argued the same position in the 14th century, today commonly referred to as “nominalism”. But given that science doesn’t yet have a respected community of specialists providing it with agreed upon epistemological principles like this from which to work, (not to mention metaphysical or axiological), it seems to me that it suffers heavily.

My point is that if you want to use the term “belief” in a dispositional capacity, then you should be permitted to do so. Or if you want to use it to representationally reference a component of consciousness itself rather than observed behavior, then that should be considered just as legitimate. But either way I think we should all be obligated to clarify our meanings at least occasionally so that people might effectively assess what we’re actually saying rather than things we aren’t.

I’d rather not belittle traditional philosophy for failing to reach agreement on this matter in my favor or otherwise however. Culturally I think it would be a shame if philosophers a thousand years from now weren’t pondering the same questions that are being pondering now, or were being pondering a thousand years ago. Thus I’d like for a new community of “meta scientists” to form with the singular purpose of providing scientists with agreed upon principles of metaphysics, epistemology, and axiology from which to do science more effectively than it’s been done in the past.

In a practical sense however, what’s the difference between the dispositional versus representational positions on belief? Observe that in coming decades scientists might develop an effective neurological conception of consciousness. In that case belief could be characterized in those specific terms. For example I suspect it will be empirically determined that consciousness resides in the right sort of neuron produced electromagnetic field. Thus belief and all other elements of consciousness might be reduced back to this specific variety of physics. But even in that case it should not be wrong to define belief in a dispositional way. Thus if you tend to treat people in different ways based upon your perception of their race, then you wouldn’t “believe” that all races of people essentially function the same. Of course you might still believe this neurologically, though that would be a different conception of “belief” that would be erroneous to conflate.

Can't say I understand the objection to dispositions being causal. To your example of your glass mug breaking when you drove off with it on the car, to me it's just a logical AND gate type situation. You leaving it on the top of the car is part of the cause, but isn't by itself sufficient. If the mug had been metal, it might have been fine, or maybe just scuffed up. Likewise if you'd remembered to take it down and put it in your cup holder, all would have been fine. For a breaking to occur, it needed to have some degree of fragility AND it needed to be in a situation where that fragility would result in it breaking. Neither by itself was sufficient.

I realize I'm probably missing something, but the overdeterminism arguments usually raised for these sorts of things, I think, only have force if we're being rigid about causes. Both a small and large rock may break a window, but the large one's additional kinetic energy may send the pieces further out and have other effects. Even in the case of an OR gate in a computer, if both conditions are true, it sill only results in the output being true, but the extra energy probably results in more waste heat.

Mike

Quick clarification Mike. He didn’t say that dispositions aren’t “causal”, but rather aren’t “causes”. Fragility for example is causal, though it doesn’t cause breakage in itself. Instead this term is meant to reflect a propensity for breakage. Similarly it would seem that dispositions cause nothing in themselves even when they do represent causal elements of existence.

Eric, so the disposition isn't 100% the cause of behavior, but then neither is the thing we're electing to call "the cause", since without the disposition it couldn't result in the effect. Still a logical AND gate as far as I can see.

That’s his point Mike. A disposition shouldn’t provide enough for a cause. The title of the post is “Beliefs don’t need to be causes (if dispositions aren’t)”. Apparently it’s in response to some criticism against his position that I haven’t read. In a causal world there should of course be countless perpetual ANDs that occur as things happen.

A better question might be, do you find fault with his dispositional conception of belief? Thus anything can have “belief” as long as it acts like it believes? Even when its head is full of pudding? Given the lure of functionalism I’d think you’d like that conception of “belief”. I’m less happy with such notions, though can’t object when explicit definitions are provided. All I can technically say is that I don’t believe in magic, as well as illustrate the magical nature of popular consciousness proposals (which thus encompass belief proposals) that reside under titles like “functionalism”, “computationalism”, and “illusionism”. I like to contrast them with one specific proposal that might empirically be demonstrated to function through worldly causal dynamics some day, and thus diverges from the many quite unfalsifiable proposals on the market today.

I have no problem with the disposition view. Except to me the dispositions seem complex enough that other labels can work equally well, like representations and predictions. It's just a matter of how we choose to divide up the causal chains.

And thus the need for a dedicated community of respected meta scientists to serve as rule makers which oversee the function of science itself…

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/08/27/magazine/daniel-dennett-interview.html

NY Times today, when your 80 0r more we tend to sum things up with endings...

...Are beginnings and endings the same though...

I am pretty sure there is more to life than beginnings and endings...

Post a Comment